Future Grandmasters of The Attention Game

How the coming flood of AI-generated content might actually free the soul of Internet

“Play the opening like a book, the middle game like a magician, and the endgame like a machine.” — Rudolf Spielmann

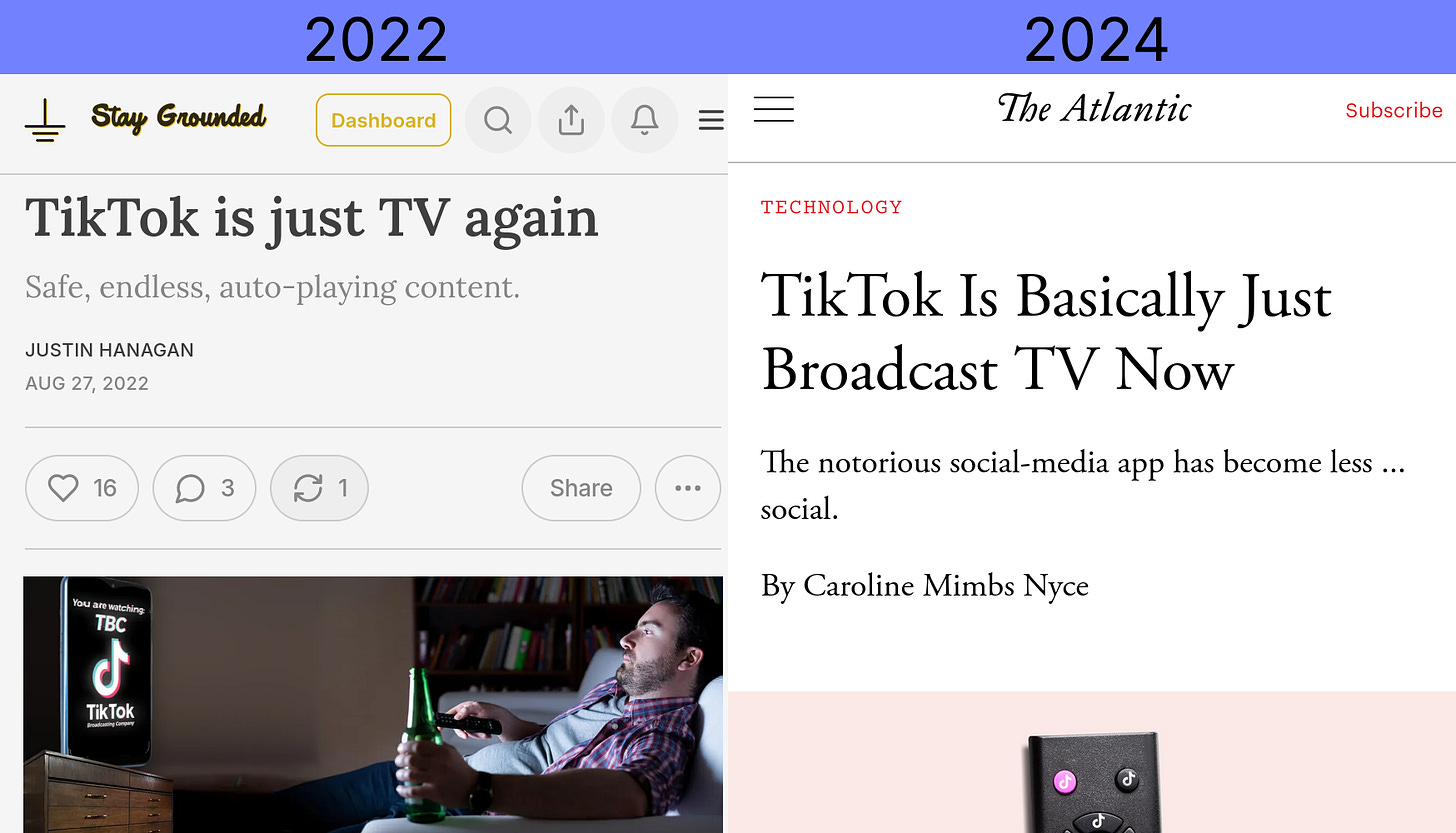

Lately, admirers of culture have been justifiably worried that human-made content on the Internet is on its way to getting crowded-out by a looming tidal wave of AI-generated crap. As “AI” “content” becomes cheaper and easier to produce, it does appear like crap waves are in fact, a-comin’, and will threaten some beloved institutions like Wikipedia, but I’m increasingly convinced that the only parts of the Internet facing a truly existential risk are the parts that gamify human attention for profit. And that the ruination of those places may actually in the long run improve Internet culture, similar to how journalism has been improving after everyone had to stop pretending Twitter was ever a town square.

For decades, media —especially “social” media— companies, have been blurring a line between content created to meaningfully connect with an audience and that which is created to influence consumer behavior. Social media platforms allow anyone (anything) to post, and reward with money and attention those posters who best enable the platform to profit. It stands to reason that if AI-generated content one day becomes indistinguishable from human made content (not a foregone conclusion but let’s assume) then any place that:

Publishes user submitted content

Does not put a strong emphasis on curating, editing, or otherwise moderating that content

will be the most vulnerable to the AI-hypercharged late-stages of enshittification. Generative AI will not break “the Internet”, it will only go where it’s allowed (Weather.com, presumably, will be fine). But if the big platforms don’t fundamentally change how they operate, “AI” could very well break the business models of Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and others. Or if not break exactly, at least reveal what they offer for what it really is: an addictive product more akin to gambling or smoking than it ever was to “connecting” people.

In this essay I want to explore what I feel is the logical conclusion of what happens if these “AI” programs manage to live up to their hype, gain the ability to create actual content instead of just stock media, and make the task of achieving virality on social media so convenient that anyone with a computer can out-attention grab the world champion grandmasters of attention-grabbing: social media marketers. But before that, I want to talk about a different kind of grandmaster, and more specifically, what makes them so interesting in the first place.

Part I - What’s Interesting?

Last month, OpenAI revealed “Sora”, its video-generating software. It’s really impressive and if you ask me, also extremely creepy. There’s something about the inconstant, unpredictable nature of the videos, and their fluid, dreamlike visuals that —for me at least— put Sora’s outputs right in the bottom-bottomest pit of the uncanny valley.

But Sora is impressive. Like all of this new generative AI software, the actual stuff they produce is only interesting insofar as how wholly uninteresting so much of it manages to be. It’s not interesting that Sora does what it says on the tin. What’s impressive is that people are building machines that can do this:

In my last post I talked about “convenience” and how shiny new tech often “makes convenient” activities everyone liked spending their time on. As an example, imagine if some startup invents a “meal in a pill”, and within a few years it puts restaurants out of business and also workers won’t get lunch breaks. But hey, so convenient right? Towards the end of that post I had this to say about generative “AI”:

The reason work doesn’t decrease when productivity increases is because companies understand they’re not paying workers for results, they’re paying for effort. Effort is the thing that humans find valuable, and making a task more convenient by definition decreases the effort that task takes. This is why clicking a button on Facebook does not make you friends with someone. It’s why we still have chess competitions despite computers far outperforming the greatest grandmasters.

Nobody is directly impressed by the chess abilities of a computer when it’s doing what humans designed it to do. What is interesting about a chess-playing computer is not that it’s good at chess, it’s that it exists at all. The interesting thing about a chess-playing computer is that some former tree-dwelling primates arranged tiny bits of metal and silicon in such a way as to coerce the universe into playing a game better than any other tree-dwelling primate could dream to.

“Interesting” and “impressive” are not properties inherent to the universe. They are concepts humans made up to describe things in relation to ourselves. The words don’t apply if life is not involved. Venus’ “ability” to go around the Sun is not impressive, but put a couple of former tree-dwelling primates into a capsule and land it safely on the Moon? (i cri evrytiem). Anytime you see the word “interesting” or “impressive”, especially when describing tech, (and gawd, especially “AI” tech), add the words “to humans” after. Dall-E is interesting to humans. Sora is impressive to humans. Without humans to be impressed, these things are just objects following the laws of physics.

When Gary Kasparov lost to Deep Blue in 1997 —the first defeat of a world chess champion by a computer— it was a significantly more interesting event (to humans) than Deep Blue losing to whatever better chess-playing computer came next. Notice that Wikipedia has a list of “Human vs computer chess matches” but not a list of “Computer vs computer” matches because Wikipedia is made for humans and computer-computer matches are just frankly not very interesting. The computers themselves are interesting, because they were built by people. But the fact that they are obeying the laws of physics is not. In fact, in 2006, less than a decade after Kasparov lost that landmark match, the New York Times reported on computer chess’ rapid decline into uninterestingness:

Today’s outcome may end the interest in future chess matches between human champions and computers, according to Monty Newborn, a professor of computer science at McGill University. Professor Newborn said of future matches: “I don’t know what one could get out of it at this point.”

Computers playing chess was very interesting (to humans) until they got consistently better than us and it suddenly wasn’t. These matches at the turn of the millennium represent the pinnacle of public interest in the sport after which it rapidly declined. “Less convenient”, “Inferior” Human vs human chess, of course, lives on, and is arguably more popular, more interesting, than ever. To paraphrase professor McGill, there’s still a lot to get out of it.

II - The Rules of the Game

The stuff that appears in our “For You” feeds appear organic. When we see “viral” content we assume that the reason it’s popular is because, like a natural virus, a large number of humans were not immune to it(s’ charms). “Going viral” implies randomness —a gene mutation that translates into a competitive edge— but it’s not how attention works on social media. As researchers at the Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure discovered, it’s not random evolution that causes virality, it’s intelligent design:

Popularity [on YouTube] is almost entirely algorithmic: We found little correlation between subscribers and views, reflecting how YouTube recommendations, and not subscriptions, are the primary drivers of traffic on the site.

Like chess, commercial social algorithmic media is a game played with rules. Those rules are called “The Algorithm” and the prize to winners is increased attention aka, “going viral”. But it’s getting harder and harder for individual creators to both create, and have time left over to play this game of attention. As artist

That labor [demanded by big tech] amounts to constant self-promotion in the form of cheap trend-following, ever-changing posting strategies, and the nagging feeling that what you are really doing with your time is marketing, not art. Under the tyranny of algorithmic media distribution, artists, authors — anyone whose work concerns itself with what it means to be human — now have to be entrepreneurs, too.

She goes on:

Self-promotion sucks. It is actually very boring and not that fun to produce TikTok videos or to learn email marketing for this purpose.

What this implies is that a creator’s success or failure at The Algorithm Game is determined, not by the time and effort spent creating interesting, meaningful content, but time and effort spent appeasing the algorithm. The artists who foolishly spend most of their effort on making good, meaningful, art will always lose the game to those who focus on marketing. It also implies that the content seen most widely —the viral stuff— is the content that had the least actual thought put into it. The algorithm (along with the corporate executives) don’t understand what art is or what “value” even means beyond a financial sense. It only understands what is likely to turn a profit.

III - Algorithms, not audiences.

The business model of algorithmic media demands endless fresh content from creators because well, that’s what keeps users addicted. The goal for companies is to keep users scrolling, and not connecting too deeply with any particular creator because gatekeeping access to the audience is what gives platforms power over creators who (need I remind you) make the stuff audiences actually want to see. By controlling access, companies can prevent creators from ever amassing enough power of their own to leave their platform.

To prevent creators from becoming more interesting than the platform itself (and thus gaining the power to leave) the companies have engineered a rule set (The Algorithm) that provides rewards only to creators who can meet its ever-changing demands. This not only means always posting new, novel content, and doing it frequently, but not doing anything too weird or challenging that might cause users to think or feel too deeply. The goal is to keep users perpetually distracted and unsteady while also maximizing overall time spent there. Think: the digital version of a windowless confusingly-structured casino main floor. Always something shiny to distract, all of it in service to the singular goal of profit.

The most successful players of the social media game are those who recognize that “their” audiences are an illusion, and perform instead directly for the algorithm. You can see this in action with channels like MrBeast, the most obvious example I know of effuse, inorganic content produced not with the goal of meaningfully connecting with an audience, but of grabbing their attention in the exact light-touch way the algorithm prefers: High effort, low stakes.

Make no mistake, MrBeast is very, very good at The Algorithm Game. He is the algorithmic media equivalent of a human chess Grandmaster. Seriously, go to his channel, look at the first few videos and tell me you weren’t a little tempted to click on a thumbnail. When it comes to the algorithm game, MrBeast is like Gary Kasparov in 1995, the undisputed world champion. But every time GenAI improves, his position at the top looks more and more vulnerable.

These days, anyone with a smartphone can reliably outperform a chess grandmaster. Let’s assume for a moment that the promises of the big tech corporations are true (lol), and that AI-generated content will one day soon be indistinguishable to a layman from human-made content. Can Mr Beast compete in an arena where anyone with a decent laptop can type “Generate a short video featuring the latest trend, in a similar but legally distinct style to Mr Beast”?

Well, first of all, before the time comes when anyone could do that, the person who would absolutely do that is Mr Beast. It’s clear he views content purely as a means to an end, and if his team can more conveniently make that content, why wouldn’t they? Social media rewards efficiency. But audiences don’t care about what content is most efficiently made. They care if something is interesting, and as we saw with computer chess, novelty can only be interesting for so long once there are no humans involved. The question is, will audiences stick around these platforms —will they be interested in what’s going on there— as they realize that the content itself has less and less actual human involvement in its creation?

Conclusion - What’s Next

I suspect some percentage of users won’t care if humans had a hand in the content creation or not. After all, some people pay money to “play” slot machines, alone, in windowless casinos, for hours. Casinos target those people hard, and it’s likely the algorithmic media companies will find a similar “audience” willing to scroll computer-made “content” alone for hours too. Whether it’s enough to sustain the business model is anyone’s guess. But even if they stay up and running, the public perception of these “services” will likely change once social media is deprived of the last pretense that anything “social” is going on1.

There’s a tempting feeling of schadenfreude that comes with imaging the big tech monopolies getting devoured by a creation born from their own greed. There’s a poetic justice to the idea of an AI bot swarm overwhelming platforms by being really good at doing all the stupid, menial labor and adjustments they have been demanding from human artists for years. And I do think it’ll happen, just not all at once. And while we may be approaching a “Kasparov vs Deep Blue moment” for the attention game, most of the pain is, I fear, still ahead.

But the winds of perception are changing. I had feelings surrounding the healthfulness of social media for years before I read this landmark piece by

wherein he described social media as “addictive” —the first time I can recall that word not being used as a substitute for “fun”— and it hit me in the gut. And back then, social media was a lot more social! It was easier to pretend something isn’t harmful when lots of real people were involved.Since then, I have been pontificating (first to my friends, then later in this newsletter when they all changed phone numbers and forgot to tell me) on the mental, emotional, and civic harm social media can cause, while trying to illustrate the reason I believe the bad stuff is not just some natural, unavoidable outgrowth of what happens when you plug a bunch of computers together, but a specific product born of corporate incentives.

And yet it seems that only recently —specifically around the time when Elon bought Twitter— that a majority of the posting class is coming around to the idea that maybe this stuff is not great for us:

My point is that tech moves fast at creating addictive stuff, but the public, often even tech journalism, moves slow when it comes to recognizing it. If I’m right and generative AI is to one day cause algorithmic media to become, on-the-whole, uninteresting, it implies that in the short term, social media will get really, really “interesting” (in a bad way). More addictive, more manipulative, less grounded in reality. That’s what’s coming.

Epilogue - Not Your Daddy’s Effective Accelerationism

But someday after that, we’ll reach a point when the phrase “social media is all fake robo-crap” will be as common of knowledge as “cigarettes cause cancer” or “slot machines are a poor investment”. Adults can still smoke and slot, sure. But nobody in the developed world can say they weren’t warned of the risks. My other hope is that when that time comes, real human-made art made for connecting with human audiences can be more readily recognized by society as the valuable thing it is on its own, not only when it is put to work in service to some marketer turning a profit for some CEO.

Before that day comes, we’ll probably have another ten-ish years of people like me getting all bent out of shape, while the majority of users won’t put together that their persistent feelings of social detachment stem from these ostensibly “social” services that slowly, but increasingly will be perceived as little more than tiny slot machines, foregoing the casino chips for dopamine.

AI can’t kill the job of artist, because making art, like playing chess, is an activity people would do even if money didn’t exist. It won’t ruin socializing. But it will ruin the “game” of social media. And we’ll be better for it.

To be clear, there is very little “social” happening on these platforms now. But as long as the process of content creation itself is directed by humans there will be something interesting about it.

You are spot on in your conclusions. It looks like we have had similar experiences trying to discuss these topics with others.

Some thoughts for consideration:

If the whole premise of this more colorful dreck is better, more profitable dreck, can the massive volume of dreck and the basic state of AI break or make useless functions like search?

I posit that it already has.

After searching for images of fine art paintings, I was assailed by a deluge of AI crap. Further qualifiers like historical, classical, oil paintings , etc. didn’t change the result. I stopped after seeing ‘Formless Blob #2’ and odd colored cow paintings, along with a tasteless AI adaptation of ‘Lady with a Ferret’.

It seems every piece of digital art is Fine Art in our brave new world. Art history erased? This obfuscation is not just in images.

It appears that someone is using AI to actively obfuscate by generating low quality peer reviewed research papers and attributing them to unknown authors in 3rd world countries. Can one researcher even write 80 papers in 6 months —not to mention the actual research? That is a paper every 32 hours. It doesn’t stop media sources from quoting this accelerating mound of feces. If AI actually gets better, who will able to distinguish real research from unreal?

As for addiction, look up Raid Shadow Legends Kraken on YouTube. Can you believe people spend more than a large house payment each month on a gaming app? One Kraken spent $70k last year alone. Paying for pixels when you are assaulted by every casino trick to make you lust for that next hit of dopamine. It is legalized gambling with champion battles. This is not uncommon across lots of game types.

There is so much more, but this comment is long enough. Thanks for the great piece. It’s nice to know that someone else thinks about this too.

This sparked a random idea to use AI to totally balance my presence on social media. To basically defeat the algorithm by enforced blandness.