In One's Own Time

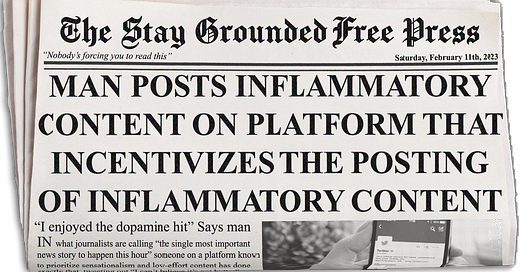

Journalists' addictions to Twitter hurt all of us. We should still go easy on them.

The day the seed planted in my brain that eventually became this newsletter I was walking and listening to journalist Kara Swisher interview… someone (I forget). It was around the same time the news broke that Facebook was caught “nudging” teenagers towards developing eating and anxiety disorders. The interview topic was about social media and how generally, well, horrible it is. I nodded along while listening, probably interjecting a few “mmhmms” of my own. I myself was working on what later became the “AIR Method” and was personally familiar with the (emotionally, politically) destabilizing effects these platforms can have.

But when the conversation got to the part about what to do about social media’s horribleness, Kara and her guest did not have many actionable suggestions. They spoke vaguely about things like regulation and pressure from corporate advertisers, while seemingly dancing around what felt like the simple and obvious fact that nobody actually needs to be on social media in the first place. Deleting one’s accounts is a perfectly valid option to avoiding the pitfalls of social media. Why did it feel like nobody1 was suggesting it?

I suspect the reason that account deletion was not brought up, is because Kara (and most journalists) are hopelessly still addicted to Twitter. To an addict, the suggestion of giving up the addictive thing can be emotionally very hard to face, even if you have been trained to look at situations as objectively as you can. I singled Ms Swisher out because I think she would likely own up to this fact, even if most other journalists wouldn’t. As any alcoholic can attest, the first step to recovery —admitting you have a problem— can be the most difficult step of all.

So many times I’ve seen newspeople rationalize their addictions by saying that they “need Twitter for their job”, which makes sense and I totally understand the need for creators of all kinds to have a social media presence. But almost without exception, a cursory glance at a given journalist’s feed will indicate that the vast majority of their near-constant time spent tweeting (and retweeting, and quote-tweeting) is wholly unrelated to anything they’re, y’know, actually journalist-ing about. If someone were just using social media for work, you’d think the content would be at least tangentially related to the work, right? …Right?

I’m not a journalist, and I won’t pretend to know the working details of the industry. It could be entirely possible that there exist some legitimate work-related reasons to interact with Twitter dozens of times per day, every day. But I think it’s much more likely that —trained journalist or not— anyone who interacts with something addictive long enough eventually gets hooked. Twenty four tweets in just as many hours sure doesn’t look like healthy boundaries. And if you your job requires an online presence, it makes it both easier to get sucked in and harder to put down.

Pooping back and forth forever

The other fact that journalists can be a little uncomfortable acknowledging is that their careers massively benefit from (and in many cases, rely upon) all the regular people that are addicted too. The content that popular users post for free is what makes these platforms worth being on at all. An influential Twitter user is both an addict and a pusher, and journalists’ addictions are hurting all of us.

Twitter’s outsized influence on society comes from the fact that so many news people use it daily and most of them also get their news via Twitter which means that their perception of the world is shaped by whatever Twitter’s toxicity-favoring algorithms present to their eyeballs. Those journalists write new stories that get posted to Twitter, which are in turn read by the other journalists on Twitter, etc. etc. etc. And what we end up with is a consumption-excretion-consumption cycle that means whatever “people are talking about” at any given time is the intellectual equivalent of poop that has been repeatedly re-eaten and processed by Twitter’s toxicity-generating digestive tract.

Writing a whole article about a tweet someone tweeted is often derided as “lazy” journalism. Which is fair to a point, but you have to remember that to the person writing the article, being on Twitter is probably at the center of their daily routine, and thus what happens there can feel like a bigger deal than outer reality would indicate. Even if someone works for a nonprofit, their perceptions of the world are heavily influenced by Twitter’s for-profit algorithms, and that influence often manifests in their work in the form of sensationalist language, a lack of nuance, and the goldfish-scale attention-span of modern “news”.

Sometimes I’ll get so mad when I hear someone in media disparage Twitter or Facebook while also using the platforms daily. “If you know how bad it is, why not take a stand and delete your account?!” I’ll yell into the void. “Your constant presence is what’s keeping other people on these platforms in the first place!”

“You are capable of getting the snowball rolling that could fix all this!”

But the truth is that getting mad at an addict rarely does anything but further entrench them in the addiction. Even if addiction wasn’t in the mix, journalists still woldn’t be eager to leave because they’d lose the following that took years to accumulate. And the followers won’t leave en-masse because the journalists are collectively providing the content they want all in one place.

The Catch-22 is that it’s the journalists (or any person of influence, but on Twitter it’s mostly the journalists) who are best positioned to free society from this ouroboros-like news cycle. And a few have taken the leap to be sure. Here are a few examples of influential people that have relied on their personal financial security and influence to leave major platforms:

Neil Young removed his music from Spotify because he is one the exceptionally rare artists who is successful enough not to need it. His absense makes Spotify a little bit worse.

Cory Doctorow doesn’t publish books on Audible2 because he’s one of the few authors successful enough that people will seek him out directly. He's probably losing money overall, but doesn’t need to be in the store to comfortably get by.

Leo Laporte is a Television and Radio host and a podcaster who is independently successful enough to not need Twitter, and he did indeed stop using it:

I actually have a Mastodon account on Leo’s instance which he’s been running since 2017. He’s spoken a lot on his show(s) about the trap that is Twitter and how awful it has made him personally feel. I have a deep respect for principled people like Leo who use their influence (and financial safety nets) to encourage others to think more critically about how these platforms work3.

Most burgeoning artists, journalists and “content creators” can’t leave the big social media companies because it’s essentially impossible today for a career to get started without them. Creators are trapped on platforms they have no control over. But there is a class of people who does have a little collective influence.

It wouldn’t take a majority of journalists to move either, only enough to establish some place (preferably public, interoperable4 with constructive incentives) as being equally worth checking out. And they wouldn’t even need to delete Twitter, altogether, they could post content to both platforms and give their followers a choice of toxic-or-not.

I’ll stop short of suggesting that “rockstar” journalists have a responsibility to leave Twitter. They have careers to look after and there is an argument to be made that if responsible journalists all leave at once, the disinformation and propaganda would take over. But it’s my hope that most of them can at least recognize that they are singularly best positioned to help society and their own mental health, by moving internet conversations out of for-profit arenas and into places built for constructive conversation.

My first ever essay posted here was titled “Nobody’s forcing you to be here” because somebody had to say it, right?

He actually has one (free) book on Audible called “Why None of My Books Are Available on Audible (And Why Amazon Owes Me $3,218.55)”

It was actually an offhand comment by Leo that inspired me to write one of my more popular posts “TikTok is just TV again”

journa.host, for one example.

‘An influential Twitter user is both an addict and a pusher’

This is the crux of the issue I would say. ‘Content creators’ face the worse of both worlds- as addicted as ‘consumers’ but not really reaping the financial rewards of those ‘influencers’ who (for whatever reason) are favoured by the algorithm.

It’s a losing game and all of the comparisons made between smartphones/social media and slot machine gambling are apt and true. Like the ‘problem gambler’, the power users of twitter and instagram are slowly but surely going broke- but spiritually instead of financially. (Although that can happen too as you waste your time and squander your career opportunities in service of using these apps all day)

I increasingly think the only way to win this game is not to play and I say this as a creator who makes my living from the internet. This does not mean to give up on creating but to automate (and increasingly ignore) the whole game of social media promotion. I figure that a regained attention span and a commitment to mastery will mean that a creator who does this will eventually thrive as their work will simply be a cut above the rest. It may be naive, it may be an unverifiable article of faith but I believe that consistent quality work is the best and truest form of promotion.

Attention and fame (and with it money) are the carrot on the end of the stick, the mythical gold at the end of the rainbow. So I have found that ignoring this, and with it accepting obscurity, anonymity, privacy and ordinariness is the only way for the creator to get off the endless treadmill.

It’s a quiet life, a less flashy life, but a more contented one when lived this way.

The work, ultimately, must be it’s own reward.

Thank you for another excellent piece, Justin. You are doing important work here.

This is something I've been struggling with as of late. I'm a small business owner who can't afford to hire a marketer, so I've been doing everything myself—and in turn have exposed myself to some of the most toxic parts of social media. I keep thinking "I wish I could just delete my account" but I can't, as it's impossible to make a living selling products online without some form of active social media presence.

I try to make high quality posts and content to bring value to people, but it's extremely disheartening when those posts do poorly while random meme I make in 30 seconds get all the engagement. It's clear that the algorithms value junk food type content over actual utility, which doesn't help the issue of addiction.

I've been slowly trying to compartmentalize and change the way I approach social media, but it's difficult. I do agree with the journalists that it would be a net positive for everyone if regulators were to step in and make these places less toxic and more useful—although that's never going to happen and is more of an optimistic pipe dream than anything else.