One of my favorite lines from King of the Hill is when Hank criticizes a christian rock band by saying to them: “Can’t you see, you’re not making Christianity better, you’re just making rock and roll worse!”

I had a conversation this week that has kind of crystalized some feelings I’ve had for a while about tech and modern society. Specifically about what “convenience” means, and what it offers. Convenience doesn’t always lead to better outcomes, and sometimes it makes the overall experience worse.

The conversation involved a friend who is becoming increasingly frustrated with their experience of all the dating apps. When someone asked this friend why they’re bothering with the apps if they find them so frustrating, my friend shrugged and replied “It’s more convenient”.

Now, call me a geriatric millennial but this felt like a weird response. First of all, I can’t imagine a romantic partner feeling too enamored to know that they were the most convenient option. But also, courtship is like, a major part of the human experience? Viewing it like a job that might benefit from being made easier seems to be missing the point that nobody is forcing (or paying) you to do it. Y’all are choosing this. You’re choosing to include swiping left and right in your threescore-and-ten.

Please don’t read this as a complete dismissal of dating apps, like all tech, they are a tool. And there are many totally valid reasons to use them which I’ll get to in a bit. What I want to examine here is an attitude surrounding some of our tech that seems to be growing. An attitude about convenience and “saved” time. A sales pitch I don’t think we should always be eager to accept.

Making Leisure Time Worse

This tongue-in-cheek post I wrote in September was inspired by a similar conversation surrounding video rental stores. Specifically how they all went out of business despite everyone I know having mainly fond memories of them! Perusing the aisles at Blockbuster mightn't've been as fun as watching the movie itself, but it was still a widely and fondly regarded part of the overall home-viewing experience. I don’t think I’ve ever heard someone say they prefer navigating the interfaces of the various streaming apps over navigating the shelves at Blockbuster, and yet that’s what we, as a society, decided to go with. Why? Because it was more convenient.

AT&T’s famously prescient “You Will” ad campaign from the early 90s lives in my head rent-free1. The accuracy of their predictions thirty years later is impressive. These ads are kind of fun to watch, so here you go if you haven’t seen them before:

The ad campaign is meant to highlight the conveniences that AT&T’s tech will bring (has brought?) to society. But when you watch them I want you to think about what activity exactly in each example is being made more convenient. Some, like the voice-powered door lock are pretty unobjectionable, because well, unlocking a door is not an activity that, to my knowledge, is widely cherished. But what about the guy doing regular-ass remote learning? Or the hiker who is interrupted by a phone call (thankfully not someone asking about his car’s warranty)? Or the man at the beach vacation house who appears to be literally working? Like- at his job? AT&T in their fantasy future, didn’t make work more convenient —freeing up time for actually enjoying a beach house— they made getting to work (or more specifically, work getting to you) convenient. And now we’ve arrived at the exact point I’d like to highlight which is that a lot of our tech that has been invented in the time since “You Will” didn’t make work better, it just made leisure time worse.

When we say an activity becomes “more convenient” we mean that it takes less effort. Usually this implies the task takes less time. Sometimes, instead of “taking less time” we like to say we’re “saving” time, but reader, please take a moment to realize that time from our perspective is not something that can be saved. We humans are allotted one minute per minute and we have no choice but to “spend” that minute the moment it is received. Like a budget surplus that disappears if not spent this fiscal quarter, our time cannot be saved, it can only be appropriated. There’s a great quote on this topic from J. Matthews in Radically Condensed Instructions for Being Just as You Are that goes like this:

"We cannot get anything ‘out’ of life. There is no little pocket, situated outside of life, where we could steal life's provisions and squirrel them away. The life of this moment has no outside.”

Those twenty four hours per day get spent — lived— whether we acquire movies via a trip to Blockbuster or by navigating the Paramount+ app. The time passes whether we swipe left, right, or close the app and go to a party. So where does the “saved” time get appropriated? Probably not on something as enjoyable as perusing the aisles at a video rental store. What it probably gets spent on is work.

One of my earlier posts to this newsletter described Facebook-style social media as “automating friendship”. I wanted readers to think about what Facebook is actually making easier for us. Facebook’s “service” is that it handles some of the “work” that being a friend involves —like catching up, or swapping stories about your day— and reduces that experience to a highlights feed that can be consumed later at one’s own convenience. Facebook does not make it easier to see your friends, it makes it easier to not see them. Facebook does not make catching up better, it just makes friendship worse.

Sometimes I think that if aliens came to earth they’d be forgiven for assuming humans don’t even like spending time catching up with friends and family because we invented machines to handle it for us while we go focus our brief lives on working and recovering from work.

Find Me in The Club

Here’s another anecdote: a few years ago, back when I was a young lad, I went to a nightclub with two former coworkers. One of them was laser-focused on getting laid that night. The other was annoyed by the former’s preoccupation, and kept regularly instructing him to “just relax and have a good time”. He pointed out (less analytically) that by viewing the evening as a goal-oriented task, and not something fun, it became work (not to mention annoying to listen to). Despite the fact that we were all doing the same thing, two of us enjoyed our time, and one of us didn’t. The only difference lie in our perspectives.

The perspective that caused my former coworker’s night out to be less fun, is shared by the “dating” apps Tinder, Match, Meetic, OkCupid, Hinge, Plenty of Fish, OurTime (all the same company!) Bumble and Badoo (a second company). These apps approach the task of finding romantic partnership as if it is work, and then they use tech to make that task more convenient.

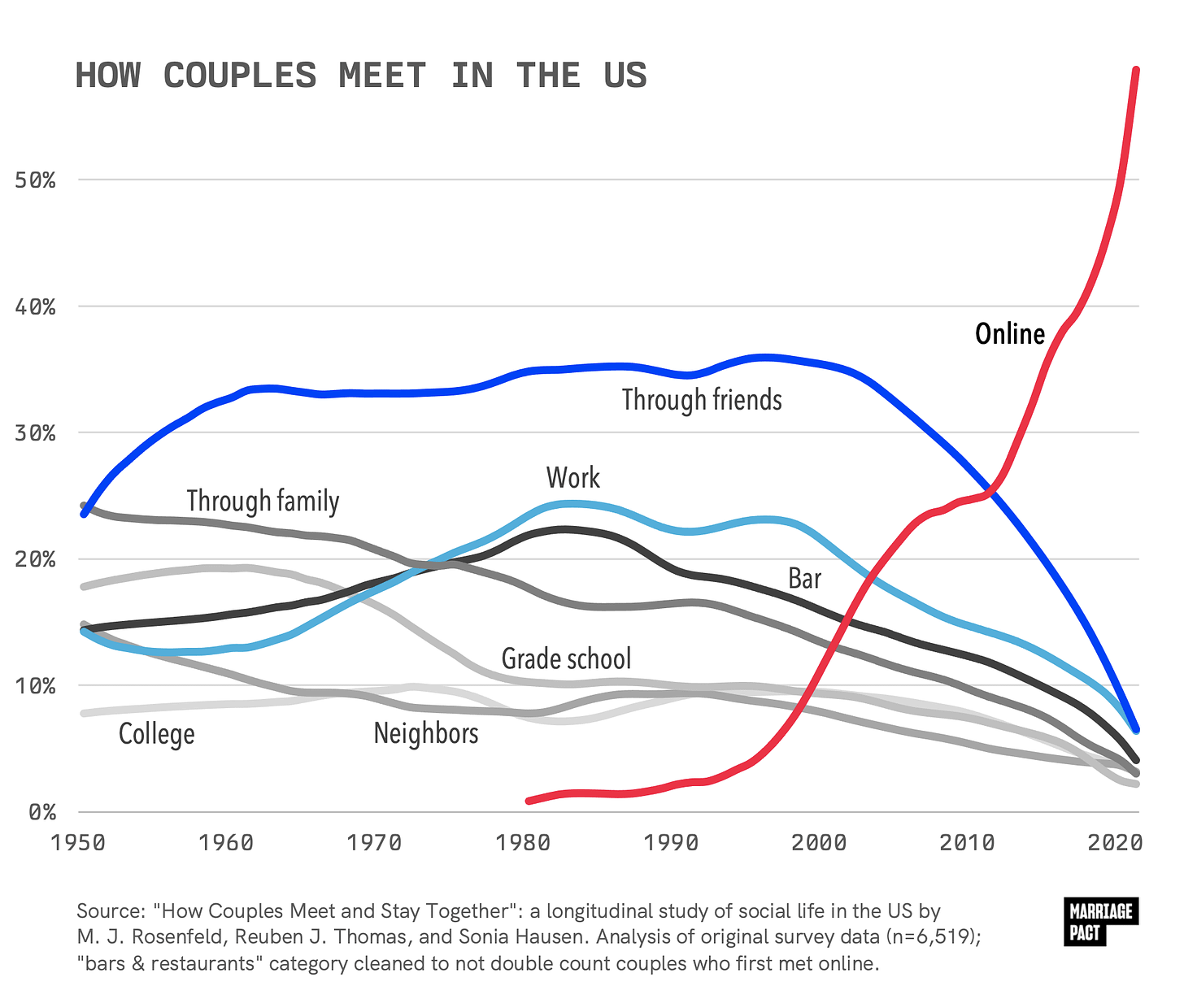

And to their credit, they succeed! Dating apps are now the most likely way for couples in the US to meet. The apps work. People are gettin’ hitched, and dating is more convenient than ever.

…But it’s not fun, is it?

Single, but who has time to mingle?

Now before y’all think I’m hopping onboard the “everything new is bad” train, there are aspects of dating that these apps have improved. There’s probably less alcohol involved, for starters. And a lot of women say it feels safer being able to “test the waters” before agreeing to meet with a strange man. But the fact remains that for a lot of young people, dating has become kind of a chore. Sure, it’s a chore that gets more convenient with every version update and algorithmic tweak2, but a chore nonetheless. A big percentage of the single-and-open-to-something population is replacing 4-5 hours of socializing in public spaces with a “more convenient” hour or two swiping left and right alone at home. Are these apps really a necessary convenience if the outcome (finding a loving partner) is more or less the same as without?

At this point, probably yes actually. As we saw in the chart, dating apps are quickly becoming the place where dating happens. My fear surrounding this is that —like the disappearance of video rental stores— we could be forcing society into a position where the least enjoyable but most convenient option becomes pretty much the only option.

So what’s the benefit to all this convenience? Where are the minutes we’re “saving” by not dating, Blockbusting, or catching up with friends being spent? Why does it feel like we have less leisure time than ever, when so much of it is ostensibly being “saved”? Remember what we discussed earlier: time is life. We have no choice but to spend it. Time “saved” is time gone forever. So when we make something more convenient, that thing becomes a smaller part of our lives. Being able to video call your grandma anytime and anywhere is meaningful if you are unable to visit her in person. But making video calling with grandma “convenient” also means it’s easier to not visit grandma.

Of course, one thing in life that always seems to use the same amount of life no matter how fancy our machines get is work. When work gets made more convenient, the “saved” time does not get replaced with leisure, but more work. Like the beach house guy from the AT&T commercial, or this happy fellow from an Apple commercial who’s work is now so convenient (thanks to Apple Knows Best™ magic) that he can do it while playing with his kids.

Because of tech, our “leisure” time increasingly consists of many small “convenient” tasks, manning the levers, pushing buttons and adjusting the knobs of machines that produce the outcomes associated with happiness —shows watched, “friends” caught up with, photos curated, spouses, uh, existing— but as long as we remain focused on future outcomes, we de-prioritize the now, the life part of living.

It’s easy to imagine a tech startup in the not-to-distant-future that promises to make vacations more convenient by just downloading unique AI-generated memories straight into your brain while automatically updating your Instagram profile with the appropriately generated photos. Here is the sales pitch for the imaginary company: “Why take a month off of work to go on vacation when this process can be done in two hours on a weekend?”

Conclusion

The reason work doesn’t decrease when productivity increases is because companies understand they’re not paying for results, they’re paying for effort. Effort is the thing that humans find valuable, and making a task more convenient by definition decreases the effort that task takes. This is why clicking a button on Facebook does not make you friends with someone. It’s why we still have chess competitions despite computers far outperforming the greatest grand masters. And it’s how we know Generative AI is in a giant hype bubble right now! A “painting” that took no human effort to create is as valuable to society as the ink it’s printed with. Heck, that printer ink is probably more valuable left unused.

The sales pitch of an inconvenient convenience isn’t something all tech does, and it’s not something new. Almost all of us geriatric millennials (and up) have at one point or another, fallen for the sales pitch of some gadget we thought would be super useful but just ended up collecting dust. That quesadilla maker for example. It doesn’t make quesadillas better, it just makes cooking worse, because I have to move it every time I need my countertop. A countertop, like life, can only hold so much, after all.

Fun fact: The “You Will” ad campaign was also the first internet banner ad (and the first clickbait)

Someone recently described dating apps to me as “AI selecting for the next generation of humans genetically most likely to do whatever AI says” and I haven’t slept since.

This reminded me of a story a volunteer at Engineers Without Borders told me.

They went to a a mountain village in South American and identified a problem that the main water supply was around a 6 mile walk away. A group of women in the village would walk 6 miles everyday to obtain the day's supply. The engineers built a well but it kept getting destroyed. They learned that it was the women who walked to the well who destroyed it. The daily walk was one of their favorite parts of their day because they got to walk and talk with their friends without anyone else interrupting.

They didn't want to "save" their time because they enjoyed doing what many people in industrialized societies would see as an inconvenience.

Justin, this was a splendid essay! I'll save this to share with my readers. It echoed perfectly, and with so many excellent examples, one of the issues Peco and I have written about as well:

"But convenience as a philosophy for living is death. A pleasant death, but still death. The question, then, we need to ask ourselves is, How many convenient boxes does it take to kill a whole society?"

Thanks for writing!